∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

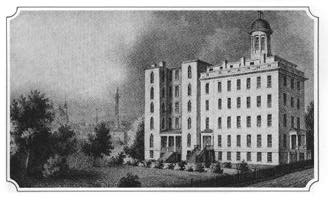

Lithograph of the Washington University Hospital (in Baltimore, Maryland), showing the building as it appeared in 1859.

On October 3, 1849, Poe was sent in a carriage to the Washington University Hospital of Baltimore (more widely known under its later incarnations as Church Home or Church Hospital). Some sources note the name of the institution as the Washington College Hospital, but the designation of University was apparently adopted in 1839. City directories from 1847-1848 and 1849-1850 confirm this somewhat more prestigious title. John J. Moran gives the name as both the Washington University Hospital and the Washington College University Hospital.

The exact details of Poe’s condition and treatment here are left to us only in the writings of his attending physician, Dr. John J. Moran. Unfortunately, Dr. Moran (who seems to have given up medicine after 1851 and was briefly the mayor of Falls Church, Virginia), appears to have made quite a career from 1875 until his own death in 1888 lecturing on Poe’s final days, the story growing more elaborate and intriguing with each telling. Thus, what should be the best source is actually one of the least reliable. Poe’s cousin, Neilson Poe, tried to visit on October 6 but was told that Edgar was too excitable and left without seeing him. Since Moran’s testimony is all we have, therefore, we must be satisfied with it. With that caveat, the following information is an attempt to provide a relatively cohesive summary, based on Moran’s various and often contradictory accounts.

Poe was taken to a room in one of the towers, where persons ill from drinking were usually put to avoid disturbing the other patients. Moran quickly decided, however, that Poe was not drunk and indeed had not been drinking. Since Poe’s clothing had been taken and replaced with something much more worn and garish, Moran suspected that Poe may have been robbed and mugged. Poe came in and out of consciousness, at one point refusing a glass of brandy offered as a stimulant. Moran then has Poe giving a number of absurdly flowery speeches, including “Language cannot tell the gushing well that swells, sways and sweeps, tempest-like, over me, signaling the ‘larm of death’.” Asked about his friends, Poe supposedly replied that “My best friend would be the man who gave me a pistol that I might blow out my brains.” By one of Moran’s descriptions, Poe called out the name of “Reynolds” (who has never satisfactorily been identified). At around 5:00 in the morning of Sunday, October 7, Poe died. His last words may have been “Lord, help my poor soul.”

Using the lithograph at the upper right, and based on information provided by Poe‘s attending physician, Dr. John J. Moran, the room in which Poe died was in the tower on the far left, on the second floor, above and to the left of the roof to the porch. There is some debate as to whether or not this is the correct location. A large stairway, apparently dating before 1855, currently occupies that tower and may have been there even in Poe’s day. Nonetheless, a bronze plaque marks the purported site of the room: “Here before alterations was the room in which Edgar Allan Poe died, October 7, 1849.” Another plaque, in the lobby, was donated in 1909 by Mrs. Thomas S. Cullen. It reads: “To the Memory of Edgar Allan Poe who spent his last days in this House.” At least one tradition holds that the attending physician was not Dr. Moran but Dr. William M. Cullen. Dr. Thomas Stephen Cullen (1868-1953) was a prominent physician at Johns Hopkins Hoospital for many years, and Mrs. Cullen was presumably his wife. Neither appears to have been related to Dr. William Cullen.

Moran’s description of the cause of Poe’s death is sufficiently vague that he probably did not know precisely what happened to his patient. He was apparently unaware of the fact that Poe had been diagnosed sometime earlier with a weak heart and that another physician said that he had “lesions on the brain.” The only official cause of death noted at the time comes from the Baltimore Clipper as “congestion of the brain.” Some time in 1851, Washington University Hospital was closed, a complete financial failure. Having been established in 1827 as the Washington Medical College of Baltimore (affiliated with the Washington College in Washington, Pennsylvania), it was intended as a substantial advance for medical practice and training. Incorporated in 1832, it moved from Holliday Street, near Saratoga, to a new building on Broadway in 1838. Unfortunately, it did not make any noticeable improvements in the success rates for operations, which had previously been done in the doctors’ houses. Faced with having to pay for the doctor’s services and frightened by stories of pain and mistakes made on the table, most patients preferred to die from the disease rather than the cure. Unable to make mortgage payments, the school abandoned the building in 1855. It was immediately seized by its primarily creditor, the Fells Point Savings Institution. In their haste, the prior owners left behind many of their books, surgical tools and equipment. They also neglected to remove a large number of bones and other human remains, presumably used for anatomy classes.

Local residents apparently made several attempts around 1853 to set fire to the building. The likely reason for such hostile feelings was probably the building’s grim association with body snatching. William N. Batchelor recalled, many years later, that there was a cemetery nearby where “. . . many that had been buried . . . never stayed in their grave twenty-four hours before they were on a dissecting table. Some, no doubt, were taken to Washington College” (Batchelor, Recollections, p. 4). This suspicion was effectively confirmed when a man appeared at the door at about midnight of the Batchelor family’s first day in the building in 1855. The man had with him a large bag containing a corpse and was most unhappy to find that the doctors had all left. Mr. Batchelor also recalled that, “It was said there had been people kidnapped and taken in there which made Washington College a horror to the people in the city of Baltimore. After the sun went down you hardly ever saw a person anywhere near it” (Batchelor, Recollections, p. 3). Although the specific charge may have had no merit in truth, the rumor was no doubt spread widely and the fear it inspired genuine enough.

In 1857, the building was purchased for $20,500 by an Episcopalian group and reopened as Church Home and Infirmary, a joint operation run under the control of St. Andrew’s Infirmary and the Church Home Society. (Cordell states that Church Home opened in 1854.) A cross, rescued from the old burned-out St. Pauls Church, was added to the point of the cupola. In 1943, the institution was renamed the Church Home and Hospital. Sometime after 1994, it became simply Church Hospital. After years of continuing financial difficulties, Church Hospital closed in the Spring of 1999. The building is owned by Johns Hopkins Hospital, but the most current plans are for the structure to be used for public housing or assisted living units. As part of these plans, modern additions to the building have been removed, although the interior is still substantially changed from what it was originally. The building is not open to the public.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

Directions:

Church Hospital is located at the corner of Broadway and Fairmount in East Baltimore. (See map under Images.)

From the Inner Harbor: Take Pratt Street east to Broadway. Turn left on Broadway for 3 blocks to Fairmount. Parking: On-street, metered parking is available, but very tight. Hospital parking is marked.

Note: Use caution when parking in an urban environment. Common sense dictates that you lock your car and keep any valuables out of sight.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

- Abrahams, Harold J., “Washington Medical College — Washington University School of Medicine of Baltimore,” The Extinct Medical Schools of Baltimore, Maryland, Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1969 (pp. 1-70).

- Batchelor, William N., Recollections of the East Building Before It Was Church Home & Infirmary, Baltimore: Church Home and Hospital, 1982 (edited with notes by Frederick T. Wehr). (Mr. Batchelor lived with his grandfather, a watchman, in the building from about spring of 1855 until summer of 1856. His recollections cover the failure of Washington College Hospital and some interesting details about medical practices of the time, including body snatching for dissection and study.)

- Cordell, Eugene Fauntleroy, MD, The Medical Annals of Maryland, Baltimore: Medical and Chirurgical Faculty, 1903 (pp. 85, 689-690, 692, 695, 702, and 703)

- Moran, Dr. John J., “[Letter to Maria Clemm, November 15, 1849],” in Hart and Quinn, Edgar Allan Poe Letters and Documents in the Enoch Pratt Library, New York; Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, 1941.

- Moran, Dr. John J., “Official Memoranda of the Death of Edgar A. Poe,” New York Herald, October 28, 1875.

- Moran, Dr. John J., A Defense of Edgar Allan Poe, Washington; William F. Boogher, 1885.

- Robinson, Judith, Ensign on a Hill: The Story of Church Home and Hospital and its School of Nursing (1854-1954), Baltimore: Church Home and Hospital, 1954.

- Wehr, Frederick T., Poe Died Here: Recollections of Church Home & Hospital (1926-1994), Baltimore: Church Home and Hospital, 1994.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

[S:1 - JAS] - Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Baltimore - Church Hospital (Site of Poe’s Death)