∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

[section B, page 2:]

Facts About Mistake

In Marking Original

Burial Place Of Poe

Miss Evans, Who Visited Westminster Churchyard And Talked With Sexton, Long Since Dead, Who Helped Bury The Poet And To Move The Body To Its Present Resting Place, Discovers That Tablet Marks Wrong Spot.

——————

By MAY GARRETTSON EVANS.

——————

ORIGINAL BURIAL PLACE OF

EDGAR ALLAN POE

From

OCTOBER 9, 1849,

Until

NOVEMBER

17, 1875.

POE-LOVING townsman and stranger have paused reverently before this inscription on a gravestone that has stood in old Westminster Churchyard for the past eight years. But they have paused, I am convinced, in the wrong spot. The place where the body of Edgar Allan Poe really was first buried, and rested for 26 years, lies nameless and unmarked in another lot. Through some mistake, only recently discovered, the stone was set up in the lot of the late Septimus Tustin, over against the east wall, instead of in that of the poet's forbears. The memorial was given by the late Orrin C. Painter, public-spirited citizen and Poe enthusiast, to mark the original grave.

How the mistake occurred no one knows. Septimus Paul Tustin, the Baltimore civil engineer and surveyor, learned a few days ago for the first time of the placement of the stone in his grandfather's lot, No. 38. “There is no tradition in our family,” he “that the body of Poe ever lay there.” S. Johnson Poe and Edgar Allan Poe, the Baltimore lawyers and kinsmen of the poet, were equally surprised to hear of the location of the memorial, as their family chronicles record explicitly that the original interment of Poe was in his grandfather's lot, No. 27. The plat of the graveyard and other old documents in the possession of the trustees also show that the Poe lot is No. 27. In this lot are the bones of Poe's grandfather, Gen. David Poe, gallant soldier of the Revolution and friend of Washington and of Lafayette. With the approval of Mr. Tustin and of the Poe family, the trustees of the graveyard have authorized the removal of the stone to the one-time grave of Poe.

As in the case of this memorial, singular mishaps have attended two other attempts to mark with enduring stone the original place of burial. It seemed as if the poet's first grave had been destined to be “nameless here forevermore.”

Some years after the death of Poe, a white marble headstone was ordered for his grave, it is said, by his cousin, the late Judge Neilson Poe. The tablet was standing completed in the marbleyard, which adjoined the tracks of the Northern Central Railroad. A few days before it was to be erected a freight train ran off the track, broke down the fence and smashed the first Poe monument to pieces.

The next attempt to mark the grave was made by the sexton who had helped to bury Poe, the late George W. Spence — I had it from the old man himself. In order that the exact location of the grave might be pointed out to visitors, Spence placed on it a bit of sandstone, containing the figure “80,” a fragment of one of the markers used to number lots — Poe's only gravestone until 1875. When, in that year, the body was transferred to its present resting place, under the monument at the northwest corner of the cemetery, assistant sexton, so Spence told me, took possession of the fragment of sandstone and sold it to a relic hunter for 50 cents or a dollar. Thus disappeared the second Poe “monument.”

A Talk With The Sexton.

My acquaintance of more than a quarter of a century ago with the sexton indirectly [column 2:] led to the recent discovery that the monument designed to memorialize the original grave of Poe had been wrongly placed. On my first pilgrimage to the historic graveyard I found that Spence actually lived among the graves and vaults under the chapel of Westminster Church. In Poe's day there were no buildings in the graveyard. When, several years after his death, church and chapel were erected, the foundations were built in the form of open crypts, in order not to violate many of the ancient tombs. In a corner of a low-arched crypt Spence had set up his household gods.

“I had a nice room up town,” he explained. “but I like this better. It's more quiet and independent.” Certainly the living disturbed him little by day and the dead not at all by night.

He hospitably invited me into this strangest of domiciles. A few domestic comforts made the place homey, incongruous as they were in their setting. An old-time, square elevated tomb, topped off with its flat marble slab, made a perfectly good table. All about us stretched the dim reaches of the crypt. Gray, crumbling headstones and solid, iron-doored vaults were but vaguely outlined gloom, even though the sun was shining brightly on grass and gravestones without.

We became very chummy. As we chatted together amid tombs of Revolutionary heroes and brave pioneers it came out that mine host had been serving in the place, man and boy, for nearly three-score years and ten.

“Oh!” I exclaimed, after a hurried calculation, “you must have been here when Poe was buried.” [column 3:]

“Why, Miss,” he answered, “I helped to bury him.”

“Then tell me every single thing you can remember about it?” I begged.

Expanding in the congenial atmosphere of his own queer hearthstone, the old man dug out of the recesses of his memory, bit by bit, all that he knew [column 4:] concerning the great American literary genius.

“Mr. Poe himself used to wander about the burying ground now and then,” he told me. “I remember plainly his looks and his manners as he went hunting about among the graves. He was always ‘very quiet and thoughtful, it appeared [column 5:] to me. Sometimes he would stand looking at the graves of the Poes, and sometimes he would wander about among the others, examining the names and dates. Once in a while, but not often, he would ask a question about some person, or how this one was related to that one, and the like. When I met him in the streets he would sometimes say ‘Good morning’ or ‘Good evening,’ and sometimes he wouldn't.

“Well, I was mighty surprised to hear of his death. I had notice to make arrangements for the burial on October 9. It was a gloomy days; not raining, but just raw and threatening. You would have been surprised to see that funeral procession. Nobody would have thought it was some great person. There was just the hearse, with one hack coming after it. There wasn't a flower. In the hack was the preacher, Mr. Clemm, Judge Poe, Mr. Herring and another gentleman. That was all — just, four, besides the grave-digger and me. It didn't take long to get the work over. The preacher said the burial service and the benediction. Then the four gentlemen went away.

“Some time after this, somebody started the story in the papers that Mr. Poe had been buried like a dog. Now, that isn't true at all. The funeral was very quiet; there wasn't any show or fuss. But there wasn't anything wrong with the way the body was buried. Come, I’ll show you just where the old grave was.

“This is the spot,” said Spence, pointing to an expanse of ground, not far from the crypt under the chapel where the sexton had made his home. Standing there in the weeds in the quaint burying-ground, at the side of the old grave-digger, I could conjure up in fancy the unpretentious funeral train; the raw day; the six men gathered about open grave; the benediction.

True Story Of Burial.

Several days afterward I learned that Spence's memory had not been at fault. I had read the widely published statement of Dr. J. J. Moran, the physician who was with Poe in his last illness, that a large concourse of distinguished folk attended his funeral. Puzzled by the discrepancy in the two accounts, I bethought me of an acquaintance, the venerable Methodist minister, the late Rev. W. T. D. Clemm, kinsman of Poe [column 6:] and of Virginia, his wife, the “preacher” of the sexton's story.

“There were only four or five of us at the funeral,” Mr. Clemm assured me. “I had prepared a funeral oration for the occasion, but I did not deliver it.”

A few days ago I came upon additional confirmation of the sexton's story, in asked the form of an old account of the burial by another member of the little funeral party. Henry Herring, who had married into the Poe family. “He was buried,” Mr. Herring wrote, “in his grandfather's (David Poe) lot near the center of the graveyard, wherein were buried his grandmother and several others of the who family. I furnished a neat mahogany coffin, and Mr. Neilson Poe the hack and the hearse. Mr. Neilson Poe, Judge number Nelson and myself, together with Mr. Chrales [[Charles]] Sutler [[Suter]], the undertaker, were the only persons attending the funeral.”

We know, then, that Edgar Allan Poe was buried “decently and in order.”

On another autumn day, 26 years after the burial, the sexton was called upon to assist in a very different memorial ceremony over the bones of the poet. This time there were orations, music, flowers, crowds. It was for the dedication of the new monument. The body of Poe had been disinterred several the days before by Spence and removed to the lot where it now rests, at the corner of Fayette and Greene streets, under the monument erected through the efforts of the late Miss Sara Sigourney Rice and other public school teachers. You can view it readily through the handsome open-work iron gate on Fayette street, the gift of Mr. Painter.

Of this occasion, too, the keeper had something to tell. “Only the skeleton was left,” he said. “When the pickaxes struck against the coffin it was found that the wood was pretty well gone. We had to put the bones into another box, about two and a half feet long. When this was put into the new grave I laid all the pieces of the old coffin in the grave, too. That is, nearly all. Several big splinters got broken off, and they were kept as souvenirs by a reporter and a policeman, I think.” (It must have been a SUN reporter, for a venerable member of the staff once showed me his mahogany penholder, which, he said, had been made from a splinter of Poe's coffin.)

“A few years before this,” the sexton [column 7:] rambled on, “I had buried Mr. Poe's mother-in-law, Mrs. Maria Clemm, in the family lot. When the monument put up the committee didn't want to have her body moved with Mr. Poe's. But I begged them to because she had asked me to lay her by the side of her boy. So we buried her under the new monument. Later on they brought to Baltimore the body of young Mrs. Poe and we buried it at the side of the monument.”

I often ran in on the old sexton after this, and one day I took with me a friend who was an admirable amateur photographer (George O. Brown, then a fellow-worker on the staff of THE SUN). A number of photographs were taken, including one of the sexton sitting in the arch of his crypt, and another of the first Poe grave and its surroundings.

A Startling Discovery.

Revisiting recently, after many years, my old haunt in the rear of the church, I threaded my way amid the shadows of the silent crypt. It was more silent than ever. Gone was the grave-digger's cot; for old Spence had long since been gathered to his fathers. Outside, in one of the lots, a shining new headstone among time-stained monuments caught my [page 3:] eye — “Original Burial Place of Edgar Allan Poe from October 9, 1849, until November 17, 1875.” But it was not in the place that Spence had indicated to me! Hastening home, I turned to the faded old photographs. They confirmed my impression that the memorial had been wrongly placed. My subsequent examination of the Poe family chronicles and of the records in the possession of the trustees of the graveyard proved to me that the sexton had pointed out the exact spot.

There is at least one man living who stood by the original grave when the body was disinterred for removal to the present grave. That man is Dr. Henry E. Shepherd, the well-known Baltimore scholar and author, who delivered a memorial address at the dedication of the monument in 1875. Dr. Shepherd, on being asked concerning the location of the original grave, said that the position indicated to me by Spence coincides more closely with his memory of the location than the lot by the east wall. At the time tablet was erected Dr. Shepherd spoke, he said, to the late Eugene Didier, the noted Poe biographer, about this point, and Mr. Didier agreed with him in his impression, though nothing further was said about it at the time. Dr. Shepherd remembers distinctly the occasion of the disinterment of the bones of the poet — literally all that was left of the body. He recalls especially the good condition of the skull, the striking shape of the forehead and the perfection of the teeth.

Outsiders are prone to rail at what they regard as Baltimore's unmindfulness of her proprietorship in the bones of the poet. There has been much slurring talk — it crops up every now and then — about Poe's “neglected grave” and the desolate God's-acre. But to me the ancient churchyard, just as it is, has always seemed a fitting home for the mortal part of him who has been called “the greatest artist of death whom the world has ever seen.” In the midst of factory and office, the clanging of car bells and the rumbling of cart and truck, it is as remote from the spirit of the bustling life about it as was Poe himself from the usual and the commonplace.

All round about, one sees the names of the brave and the gallant, inscribed on old stones with stately epitaphs of the days when one's mate was a “consort” and one's widow a “relict.”

Our poet is, indeed, in a goodly fellowship in Westminster yard. Here lie the bones of Gen. John Stricker, soldier of the Revolution and commander of the third Brigade at the battle of North Point, in the second war with England. Of Col. David Harris, also a hero of the Revolution, and at the age of 73 at the battle of North Point; or, as his epitaph reads, one of “the brave defenders of this city in its hour of peril.” Of Capt. Paul Bentalou, officer of the Revolution, in whose arms Count Pulaski died at battle of Savannah. Of Gen. Samuel Smith, soldier of the Revolution, Secretary of the Navy, Mayor of Baltimore, and for 40 years in Congress.

Go, make your pilgramage [[pilgrimage]] to old Westminster yard. Do not merely stand on the sidewalk and peer in, after the manner of the hardened sightseer. Go within the gates — they are usually locked, to be sure; but if you are persevering you will somehow manage it — and do a bit of exploring on your own account. Then you will know the poet's resting-place as another Baltimore poet, Lisette Woodworth Reese, knows it —

“Stone calls to stone, and roof to roof;

Dust unto dust;

Lo, in the midst, starry, aloof —

Like white of April blown by last year's stalks

Across the gust —

A Presence walks.”

Notes:

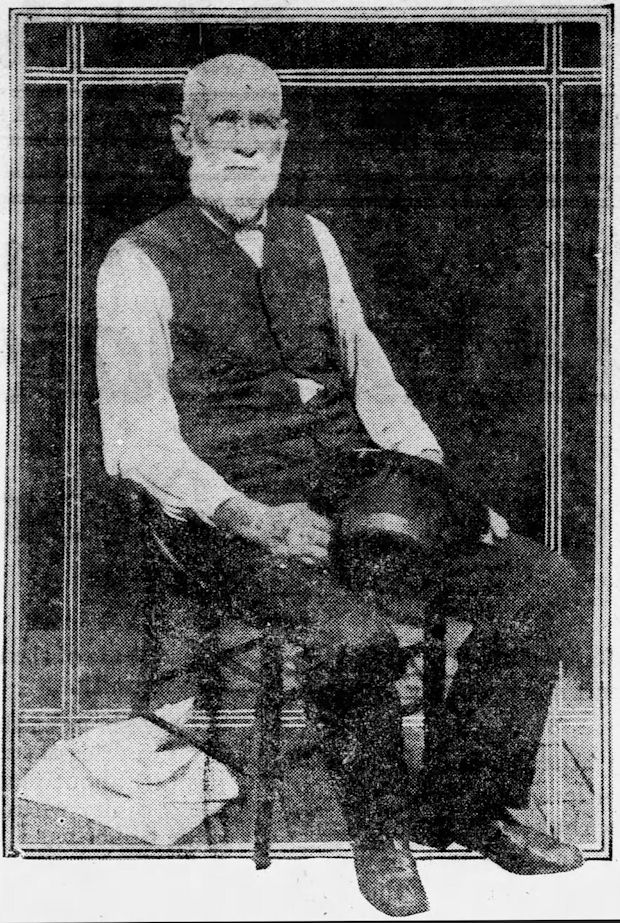

The original article is accompanied by a photograph of Mr. Spence:

With the following caption:

George W. Spence, sexton of Westminster Church for nearly 70 years. Spence died in 1899. He helped to bury Poe and to remove the body to its place under the monument.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

[S:1 - BS, 1920] - Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - A Poe Bookshelf - Facts About Mistake in Marking Original Burial Place of Poe (M. G. Evans, 1920)